Musick fyne: Scottish Church Music (up to 1603)

Alistair Warwick

This is a brief overview. Expanded articles will appear in due course.

Introduction

We are very familiar with the names of William Byrd and Thomas Tallis, perhaps also with those of Robert Parsons, Christopher Tye and John Shepherd.

But what about those from England's northern neighbour?

While the names of many English composers trip off the tongue, until recently it has been harder to name many composers writing music for the Scottish Church. However, this difficulty may perhaps be one of quantity rather than quality, partly due to "the ravages of time" and a possible loss of manuscripts following the Reformation in Scotland, which took place in 1559-60, some 18 years later than that in England.

One might well speculate that if the Catholic reformers had succeeded in reforming the Church from the inside – there were many signs that this was happening – then there might well have been a continued flourishing of "musick fyne" – art music – in Scotland. Unfortunately, however, this is merely speculation, and almost all the material we have to assess is the tantalisingly small amount that survives from the two main periods of musical growth: up to the 13th century and during the 15th and 16th centuries.

Musical growth in Scotland

Up to the thirteenth century music in both court and church flowered, including the founding of great ecclesiastical centres (with song schools) in Dunfermline, St Andrews, Glasgow and Elgin.

The 13th-century St Andrews Book (known as "W1") seems to have been compiled in or for St Andrews. In addition to a core repertory of polyphony from the Notre Dame School of Leonin and Perotin, there are varied additions dating from around 1240 including two responsories for First and Second Vespers (Evening Prayer) of St Andrew, patron not only of the town, but of the entire kingdom. The music gives us some idea of the high standard of singing at St Andrews Cathedral at this time.

Medieval liturgy and chant

For over a thousand years Scottish music, like its liturgy, seems to have had an identity both derivative and unique. This twin personality can be seen in the late thirteenth-century Inchcolm Antiphoner honouring St Columba (c. 521-597). These chants may originate from some six hundred years earlier, from shortly after the saint's death up to the tenth century.

Inchcolm (literally, "The Island of Columba"), an island on the Firth of Forth, has monastic ruins dating from the 12th century and historic links, via Dunkeld, with the Celtic monastery of Iona. A few pages remain of this Antiphoner, which escaped 16th-century destructions by being used as waste material in a book binding. Much of the music in the surviving pages of the Antiphoner comes from the standard Gregorian repertoire, but adapted to fit words relating to St Columba. However, the Magnificat Antiphon and a few other pieces seem to be unique. Could these represent a lost tradition of Celtic Chant, passed down from one generation of monks to another before being written in this Antiphoner?

Along with chants celebrating the miracles of St Kentigern (or St Mungo) – which can be found in the Sprouston Breviary (Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland) – the Inchcolm chants have a distinct personality in a similar way to the organisation and practices of the Celtic Church. The liturgy was different too, or so it at first seems, since James IV signed a printing licence in 1507 authorising

"mess bukis, manalis, matyne bukis and portuus bukis [breviaries] efter our awin Scottis use and with legendis of Scottis sanctis…"and because of the high costs involved that

"na manner of sic bukis of Salusbery us[e] be brocht to be sauld within our realme in tym cuming…" [1]

However, as Isobel Woods has demonstrated, only one liturgical book resulted from the licence: William Elphinstone's Aberdeen Breviary published in 1510. So while the liturgy remained largely that of the Use of Sarum (Salisbury), the veneration of the Saints was a different matter. Elphinstone, founder of Aberdeen University, was an intelligent, pastoral bishop intent on internal reform, and responsible for the re-discovery of the cult of Scottish saints. He produced seventy, drawn from across the country, to add to the previous handful of those who helped to

"prove Scotland's distinctive place as a European nation… [since] the province of the church in Scotland was now provided with its own holy men, as other provinces of the church universal had long had". [2]

Even if it was simply an addition of local saints to the lectionary, rather than a completely different liturgy, this addition to the sanctorale has provided some intriguing flavour.

First part of a digitised copy of the Aberdeen Breviary, as published by the Bannatyne Club (whose secretary was David Laing) (London, 1854), now in the National Library of Scotland

Fifteenth-century polyphony

Probably the earliest surviving evidence of polyphony remaining in Scotland are the Paisley Abbey fragments, discovered in 1991. These two fragments of slate contain unrelated and untexted musical notation which appears to be from the mid-fifteenth century.

Kenneth Elliott from Glasgow University [3] considers that one could be the top part of a two- or three-part polyphonic composition, while the second could either be the conclusion of a monophonic piece, or of one part of a polyphonic piece. It is possible that these slates, like other contemporary examples found in Co Louth, Ireland, and in Wells, England, might have been used as permanent methods of teaching and rehearsing for boy choristers.

The Carvor Choirbook

Robert Carvor (or Carver, otherwise known as Arnot, born c. 1484; died after 1568) was an Augustinian canon of Scone and of the Chapel Royal at Stirling.

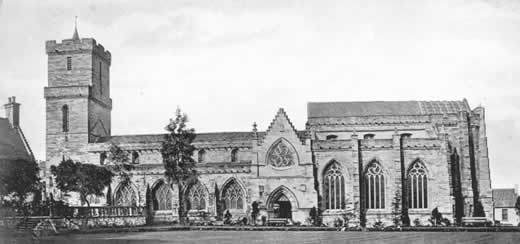

Reconstruction work for Holy Rude Church, the parish church of Stirling, was overseen by Robert Arnot (it has been suggested that this may be the same Robert Carvor or Arnot)

The Carvor Choirbook (in the National Library of Scotland), has similar repertory to the Eton Choirbook and is similar in scope to the Lambeth Palace manuscript (both contemporary sources). It contains a wide-ranging collection of vocal polyphony from Burgundy (Dufay), England (Nesbett, Lambe, Corynish and Fayrfax) and Scotland, together with Flemish-inspired works.

Carvor's compositions in the Choirbook consist of mass settings in 4, 5, 6 and 10 parts, including one built on the secular tune L'homme armé. The 10-part mass Dum sacrum mysterium may have been written for the coronation of the infant James V following the disastrous rout at Flodden in 1513. The Choirbook also contains another mass setting attributed to him, the unnamed mass for three voices. (The present author disputes the common attribution of the mass Cantate Domino in the Dowglas-Fisher Partbooks to Carvor – see Dunkeld Music Book.)

The two surviving motets by Carvor in the Choirbook are Gaude flore virginali for five voices and the 19-voice O bone Jesu. This latter, large-scale motet may have been composed for the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus, and is believed to have been a personal prayer of James IV. It consists of pillars of sound on the word "Jesu" providing a framework for very varied reduced-scoring interludes with sustained imitation, free decorative counterpoint and strong rhythmical chordal passages.

The Wode Partbooks

David Peebles (fl. 1570) had been an Augustinian canon at St Andrews Priory. After the Reformation he married a Katherine Kinnear and lived with their two sons, Andrew and Thomas, in the grounds of the Priory. His known, surviving work is to be found in one set of manuscripts, the Wode Partbooks compiled by Thomas Wode (or Wood), vicar of St Andrews.

These partbooks – which may have been intended as a gift by Wode to the infant King James VI [4] – are in two layers (or sections). The first section contains simple four-part harmonised settings, largely by Peebles, of metrical psalms from Geneva and France, together with metrical canticles, and some motets by Peebles and others. The metrical settings reflect the need of the reformers for simple music that could be sung by everyone present, rather than the specialised music for choirs apparently preferred by Peebles, whose two motets Si quis diligit me and Quam multis, Domine (a setting of verses from Psalm 3) show complete mastery of polyphonic writing, and who appears not to have been too keen to write these simple harmonisations.

Wode writes that the Prior had instructed Peebles,

being ane of the chief musitians into this land to set three pairtis to the tenor [the melody was in the tenor] and my lord cammandit the said david to leave the curiosity of the musike [i.e. to keep the settings simple]; and sa to make plaine and dulce, and sa he hes done; bot the same david he wes not earnest; bot I being cum to this toune to remaine, I wes ever requesting and solisting till they war all set… [5]

Although Peebles' preference seems to have been for musick fyne (polyphonic music), these psalm settings do show some interesting features. Indeed other composers writing settings for the Partbooks provide some settings "in Reports", i.e. in canon.

Si quis diligit me

Peebles' motet Si quis diligit me, a setting of John 14:23, has some motivic similarities to Tallis's If ye love me (John 14: 15).

A comparison of motives (original pitch and note values) from Si quis diligit me and If ye love me:

The bottom stave shows the "tenor" from the original chant, the middle line is from the additional fifth voice (by Francy Heagy, a pupil of Peebles), the top line is by Tallis.

Si quis diligit me would be a worthwhile – if rather more challenging – addition to a choir's repertory. The biggest challenge is sustaining the long notes in the tenor; sensitive doubling with a 8' flute on the organ would assist.

The opening of Peebles' Si quis diligit me (at original pitch and with original note values)

Dowglas-Fisher Partbooks (Dunkeld Music Book / Lincluden Partbooks)

Five of six partbooks remain of this collection of mass propers for feasts of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the apostle Peter, written for six and eight voices by continental composers including Certon, Lupi, Claudin, Josquin, van Wilder, Jachet and Willaert.

These partbooks are listed in the Special Collections catalogue at Edinburgh University Library as the Dunkeld Music Book (GB-EdU MS 64). Kenneth Elliott surmised that they may in fact be from Lincluden, near Dumfries.

Lincluden Priory: possibly the community from which the Dowglas-Fisher Partbooks originated

Within these partbooks there are two anonymous masses Felix namque and Cantate Domino, quite possibly by David Peebles – Kenneth Elliott ascribes Cantate Domino to Robert Carvor on the grounds of similarity to the latter composer's 5-part Mass Fera pessima; however this is unlikely – and an incomplete single voice part from the mass Jesu Christe by the English composer Thomas Ashewell.

There is also an intriguing anonymous motet Te sanctum Dominum, which the current author has tentatively ascribed to Nicholas Gombert.

Bars 31-40 of the anonymous eight-voice motet Te sanctum Dominum

(the missing 2nd bass part has been reconstructed by Alistair Warwick)

The Art of Music

An incomplete treatise of this name, dating from the second half of the sixteenth century (possibly Edinburgh, 1580) and written by "Scottish Anonymous" deals with the use of faburden (otherwise known as fauxbourdon: the way in which counter-melodies were added to a tune or air).

This compositional technique may have been a parish church style, although it also appears to have been used at the Chapel Royal. Carvor made use of this technique in his mass Pater creator omnium.

Although by 1603 the two crowns of England and Scotland had been united in one king, James VI/I, after leaving for London he returned to Scotland only once, bringing with him the singers of the English Chapel Royal. This seemed to indicate a downturn for music in Scotland. However, although "musick fyne" of the Renaissance had come to an end, Scottish music developed in other ways and forms. Much of this is still to be discovered.

Recommended listening

- Scotland's Music: Selected works from the history of Scotland's music (Linn Records, CKD008, 1992)

- A Liturgy for St Columba: Gregorian Chant from Pluscarden Abbey (Pluscarden Abbey, Elgin, 1997)

- Columba, Most Holy of Saints (Capella Nova/Alan Tavener, ASV CD GAU 129, 1992)

- The Miracles of St Kentigern (Capella Nova/Alan Tavener, ASV CD GAU 169, 1997)

-

The Music for Robert Carver

(3 volumes: Capella Nova/Alan Tavener, ASV CD GAU 124,126, 127, 1991)

-

Sacred Music for Mary, Queen of Scots

(Capella Nova/Alan Tavener, ASV CD GAU 136, 1993)

Recommended Reading

- Elliott, Kenneth ed., The Paisley Abbey Fragments (Musica Scotica, Glasgow, 1996)

- Laing, David, "An Account of the Scottish Psalter of A.D. 1566" from Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, April 1868 (view as PDF)

- Purser, John, Scotland's Music (3rd ed.: Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh 2007)

– buy from Amazon.co.uk - Ross, D James, Musick Fyne (Mercat Press, Edinburgh, 1993)

- Warwick, Alistair, Dunkeld Music Book alistairwarwick.com

- Warwick, Alistair, Wode Partbooks (St Andrews Psalter) alistairwarwick.com

- Woods Preece, Isobel (ed. Sally Harper), Our awin Scottis use

(Music of Scotland, Glasgow and Aberdeen, 2000)

– buy from Amazon.co.uk - Wormald, Jenny Court, Kirk and Community 1470-1625 (Arnold, London, 1981)

– read extracts online at Amazon.co.uk

– buy from Amazon.co.uk

See also the Wikipedia entry that references this page.

Editions

Since 1995 there have been two main initiatives to make available scholarly editions of important surviving Scottish manuscripts until now locked away in libraries:

- Musica Scotica, general editor: Kenneth Elliott, published by the University of Glasgow (www.musicascotica.org.uk)

- The Music of Scotland, general editors: Warwick Edwards and James Porter, published jointly by the Universities of Aberdeen and Glasgow (www.gla.ac.uk/departments/music/research/MOS)

Other editions include:

- Elliott, Kenneth ed., Music of Scotland 1500-1700 (3rd edition: Musica Britannica, xv, London, 1975)

- Elliott, Kenneth ed., The Complete Works of Robert Carver & Two anonymous Masses (Musica Scotica, Glasgow, 1996)

- Peebles, David, ed. Alistair Warwick, Si quis diligit me (theartofmusic.com – forthcoming)

- Antico Edition and Bardic Edition have also published editions of Carvor's music by Isobel Woods and Muriel Brown.

Edit history

An earlier version of this article first appeared in Church Music Quarterly (RSCM, June 2005).

Contact

Contact Alistair Warwick at:

Ardarroch, Glen Road, Dunblane, FK15 0GY, Scotland

+44 (0)1786 823000 |

+44 (0)7792 566349

hello(at)alistairwarwick.com